A finger hovers over a big red button, shaking. The clock ticks steadily down toward zero, with a small electrical buzz as every second slips away. Further away, a physicist slaps sun cream onto his face in the early morning darkness. His colleague sits in the car next time. “The glass stops the radiation,” he explains. “What stops the glass?” asks the sun-creamed physicist. There’s no answer, because really nobody knows what’s about to happen. They’ve run the numbers, done the theory, talked ideas around in circles. But now it’s time to press the big red button.

The Trinity test – the first detonation of an atomic weapon on 16 July 1945 in the New Mexico desert – is the centrepiece of Christopher Nolan’s biopic Oppenheimer, the event which splits his film like an atom and sends neutrons ricocheting forwards and backwards through time. Nolan’s film is a gigantic one: even while you’re enjoying it, you feel all of its 180 dense minutes. And, you know, fair enough – this is, as Matt Damon’s Lieutenant General Leslie Groves spits at one point, “the most important thing to ever happen in the history of the world”. But it might also be so vast because it packs in elements of entire Nolan’s career so far. All of the most thoroughly Nolanesque (Nolan-y? Nolanous? Nolanian?) ideas and moves are there, built up and banked over the 25 years he’s spent being our most relentlessly unusual box office juggernaut. The Trinity test sequence is the infinitely dense point where they all occur at once; the Nolan singularity, at which point strange and beautiful things happen.

Most obviously, it’s the most warlike moment in a war story which refuses to let itself get wrapped up in crass things like glory and heroism. Remember at the end of Dunkirk when Harry Styles is sure that he and his mate are going to be pariahs when they finally make it back home after their shame-faced retreat from northern France? That film is absolutely full of moments of shame and desperation, and there’s a hint of that here too in the silence which fills the firing range as the ‘gadget’ finally goes off. When Oppenheimer’s colleagues celebrate, he’s more circumspect. Here, too, is Dunkirk’s slowly-ratcheting tension in the terror of that ticking clock, and the waves of nausea that crash as the moment heaves closer. The test itself feels like a stomach-churning precipice rather than a well-trodden Wikipedia entry.

Oppenheimer’s invention comes parcelled with a paranoia about technological innovation becoming weaponised, an idea which also ran through The Dark Knight. Think of Lucius Fox warning Bruce Wayne about sneakily using Gotham’s smartphones to map out the whole city, in order to see what everyone’s up to: “Spying on 30 million people is not part of my job description.” And the existential dread in the face of a technology too powerful to be properly understood seeped into The Prestige. “Mr Angier, have you considered the cost of such a machine?” David Bowie’s Nikola Tesla asks when he’s tasked with making a device to transport Hugh Jackman’s magician across a stage. Later, when he’s built the machine, he adds a suggestion on its use: “Destroy it. Drop it to the bottom of the deepest ocean. Such a thing will bring you only misery.”

He might as well have been dropping off a nuke at Los Alamos. Whether Oppenheimer actually pulled that quote from the Bhagavad Ghita out of the back of his brain when the bomb went off – “Now I am become Death, destroyer of worlds” – as Nolan implies he did is up for debate, but there’s the sense of a clever man wading too far out of his depth and realising too late that the tide is pulling him further out. There’s horror in those deep blue eyes.

The raw, real-life terror of the Trinity test sequence becomes the biggest canvas Nolan’s ever painted on.

Even the ever-present timeframe and perspective-shuffling that’s been part of Nolan’s visual language ever since Memento can be found during Oppenheimer’s bomb sequence, albeit in more subtle form. We shift between Oppenheimer in the south bunker, Groves and some physicists slightly further away, and another set of scientists even further back – their experiences are different, based on their proximity to the blast. Time warps for Oppenheimer: lost in the silence before the shockwave hits him, the raw power of the bomb hangs in the air and stretches out the moment at which all his dreams and fears become a fiery, city-levelling reality.

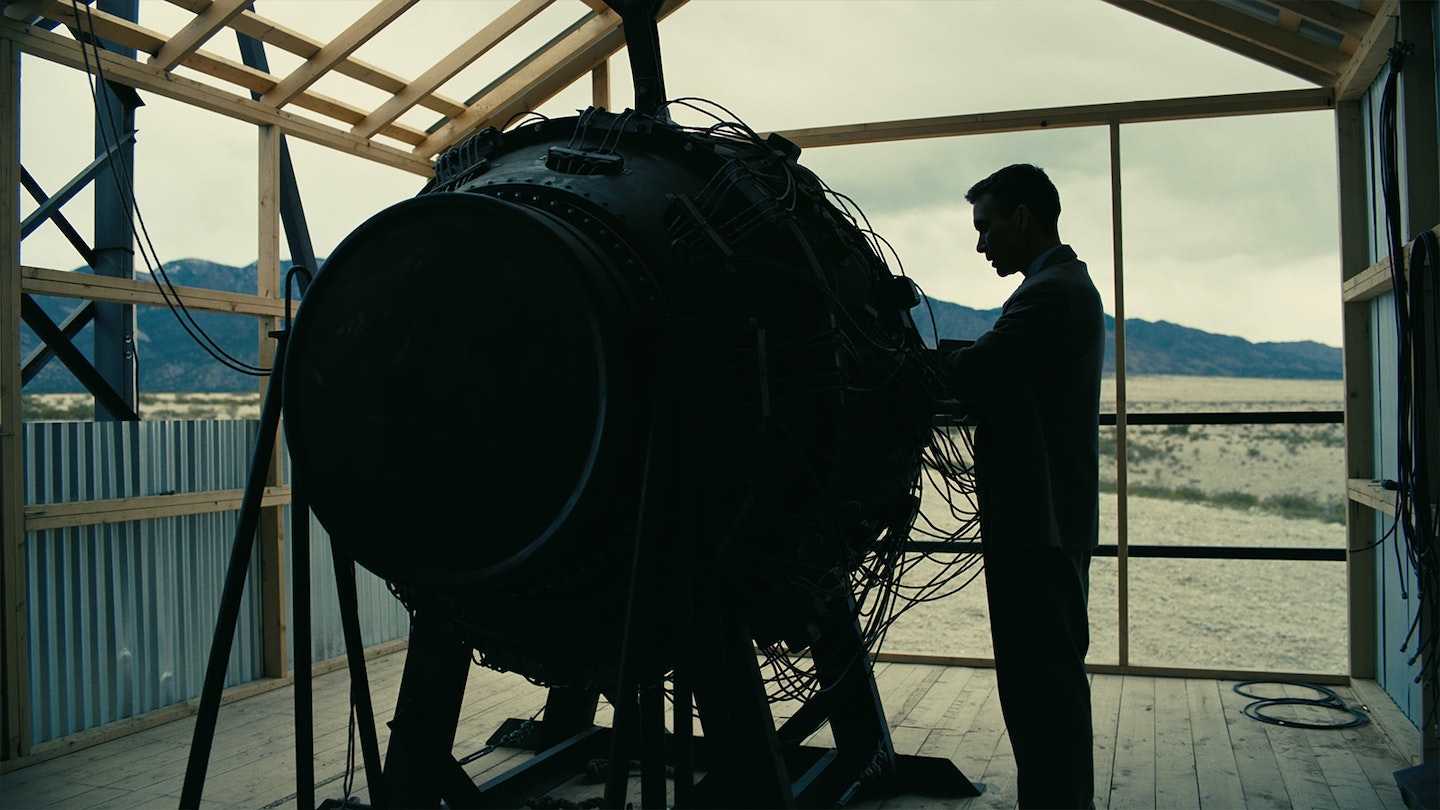

Most of all, there’s the late-Nolan insistence on doing things for real as much as possible. Ahead of release he made a great play of having recreated the Trinity test – which, we’ll remind you, was very much a nuclear explosion with the force of 25,000 tons of TNT – without any CGI, entirely in-camera with practical effects. It’s quite an achievement, and is a classic example of the director’s longstanding zeal for both Proper Cinema and handy bits of marketing which make Nolan films feel so very Nolan-like. The buzz around the Trinity sequence before Oppenheimer arrived was slightly disbelieving. Like, really? Did he… did he blow up an actual nuke? Is Christopher Nolan a nuclear power now? What if he turns into a rogue state?

That sense of disbelief at what Nolan was attempting – and the certainty that it was going to look amazing – was a big part of the Interstellar hype, which focused on his rigorousness in getting the science of black holes and transgalactic travel right, with the help of physicist Kip Thorne. In the maelstrom of confusion that timey-wimey Tenet inspired, it’s easy to forget that doing it for real – blowing up buildings both forwards and backwards, filming sequences seemingly in reverse – was a big part of that film’s appeal too. The IMAX-boosted beauty of the Trinity sequence builds on both of those films, pushing all 70mm of the frame to their limits.

In that claustrophobic hut somewhere on the dark plain, waiting for the dawn of a new sun, and potentially the destruction of the planet, there’s everything Nolan does better than anyone else – and though he’s sent Matthew McConaughey into a wormhole and bent Paris back on itself, the raw, real-life terror of the Trinity test sequence becomes the biggest canvas he’s ever painted on. It’s impossible not to be blown away by it.